By Stu Winters

A recently published peer-reviewed scientific review article published in the journal “Nature Reviews: Earth and Environment” seeks to show that terrestrial climate change is resulting in unusually rapid and/or high magnitude swings between unusually wet and dry conditions (or vice versa) relative to what is typical for a given location and season. And how such patterns are increasing on an increasingly warming earth.

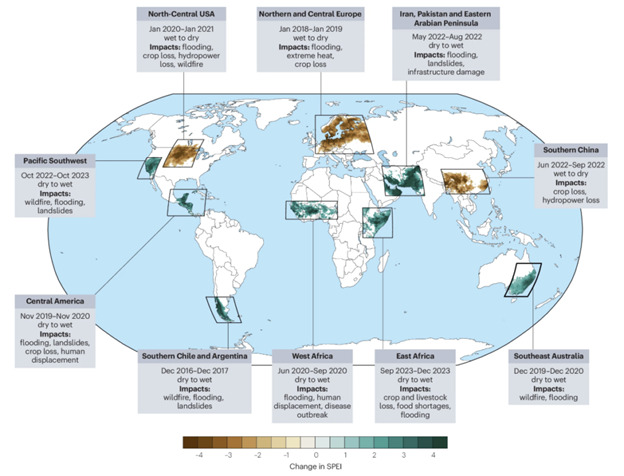

The following image, taken from the study, seeks to illustrate these swings geographically.

The researchers use the term “hydroclimate whiplash”– as encompassing unusually rapid transitions between extremely wet and extremely dry conditions.

The common thread that distinguish these phenomena are sudden and/or high-magnitude shifts between wet and dry hydrologic states – that is, floods and drought cycles – made more intense and frequent by increased climate warming.

This increase in the maximum amount of water vapor in the Earth’s atmosphere has increased with global warming since warmer air is able to hold more moisture. However, this does not mean that it increases everywhere and at all times.

“This increase in the maximum amount of water vapor that can be present in air is the main reason why we have already experienced an increase heavy precipitation events globally, and in most sub-regions–and that increase is expected to become even more widespread (nearly universal) over global land areas with further warming.”

In fact, at times and places where the atmosphere is drier (i.e., when there are not clouds and/or precipitation present), this very same thermodynamic mechanism also explains why the atmosphere has an increased propensity to evaporate water from bodies and water and the land surface.

This means that the amount of water vapor that air actually contains, versus how much it could contain, rises in a warming atmosphere, leading to rapid increases in what is known as the “vapor pressure deficit” as well as driving widespread and large increases in evaporative moisture moves from areas of greater to lesser concentrations.

This tends to drive increases in both potential flood severity as well as potential drought severity which leads to increases in wildfire intensity.

The research explains that in the case of specific regions the hypothesized changes in atmospheric circulation are likely to be consequential. In California, for instance, they will likely affect the nature of increased hydroclimate whiplash:

“…while increasing whiplash appears more or less inevitable in this part of the world, whether it comes in a more wet or dry “flavored” variety will likely depend, in large part, how the jet stream shifts seasonally over the North Pacific.”

“In our own brief analysis, we find that hydroclimate whiplash will likely continue to increase with additional global warming and likely emerge more strongly and unambiguously in more regions.”

“…These projected increases [of climate whiplash] are strongest over global land areas (though extend across most oceans, with smaller magnitude)–likely due to the amplifying effect of faster-warming continents.”

Regarding California in particular, with relevance to current climatic patterns:

“We still find increases in California hydroclimate whiplash with rising global temperatures, but the Golden State is decidedly not a global hotspot using this particular generalized metric compared to other regions that are projected to experience much larger increases….recent experience with both extreme dry and extreme wet events (and transitions between them) is indeed likely representative of future trends.”

Very relevant to current risks as a consequence of recent rainfall in the wake of wildfire devastation is the increased possibility of debris flows in steep as torrential rain falls on parched or burned soils; wildfire risk itself can be accentuated by swings from very wet to very dry conditions.

In other words weather patterns, which increasingly lurches back and forth between episodic wet and dry extremes, pose increasing risks of the sort of devastating outcomes we are now witnessing in the Los Angeles area. This is particularly acute in grassland, shrubland, and woodland environments.

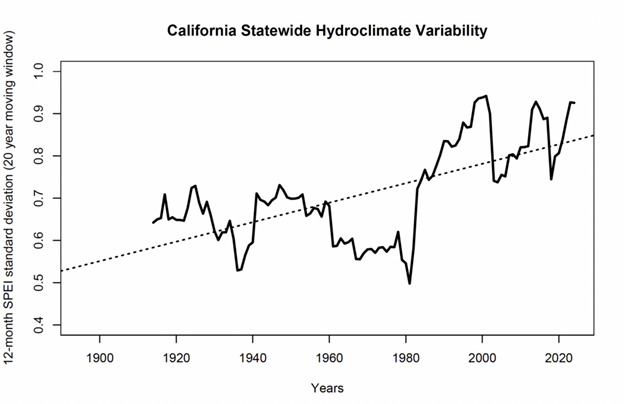

An illustrative time series depicting increased variability of California hydroclimate between 1895-2024. The solid black line represents the standard deviation of December SPEI-12 (plotted using a 20-year moving average); the dashed line represents the linear trend of this variability over the period of record (p-value <0.001).

(Data via WRCC West Wide Drought Tracker; plot by Daniel Swain)

“Very wet conditions in winters of 2023 and 2024 gave way to a record-dry start to 2025 wet season (with periods of record warmth and evaporative demand sandwiched in between). A very strong and dry downslope windstorm in early January was the proximal catalyst for the unprecedented wildfire disasters that subsequently unfolded, but the far more anomalous whiplash event that preceded it (including the failure of seasonal rains to arrive as of this mid-January writing) is what truly set the stage. Thus, continued warming, plus wider swings between extreme wet and extreme dry, are likely to increasingly interact with California’s narrowing rainy season to produce more frequent overlap between critically dry vegetation conditions and strong, dry “offshore wind” season –particularly across coastal Southern California.”[1]

It is, in view of the above, essential that scientific method be applied in planning for future climate instability as a result of an increasingly warming globe.

Capitalism, dependent as it is on short term profit maximization and the endless physical growth imperative, is inherently ill disposed to rational planning for these climatic episodes which are being increasingly revealed by research such as summarized in this article.

Therefore a rational approach requires a system geared towards decision making based upon protection and benefits for human habitation allied with the natural world. Such a system can only be socialism, where the working people collectively make democratic decisions on the basis of their common ownership of the major means of production.

(A “read-only” version of the full paper upon which this article is based is available online.[2])

[1] www.agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2021gl092843 (28-01-2025)

[2] www.nature.com/articles/s43017-024-00624-z.epdf?sharing_token=__6h7j2lsMw2qIyJGK5vf9RgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0O9RZ3Zpesp9Svwudh0S7m0ggaSvjZJGBGXdDymgcJB3fDDsWUS3-6T5tMcQiHZjaGZlQeJlRyWkrokMGlhkB7qbU9Vq2lBQj_0Gre5St07oq-nxO4Zt1JpJx32wVUtL8I%3D (28-01-2025)